Sharon McConnell-Dickerson is preserving the Mississippi Delta blues with her own two hands. She’s doing it by creating molds of some of the most influential blues musicians of our time.

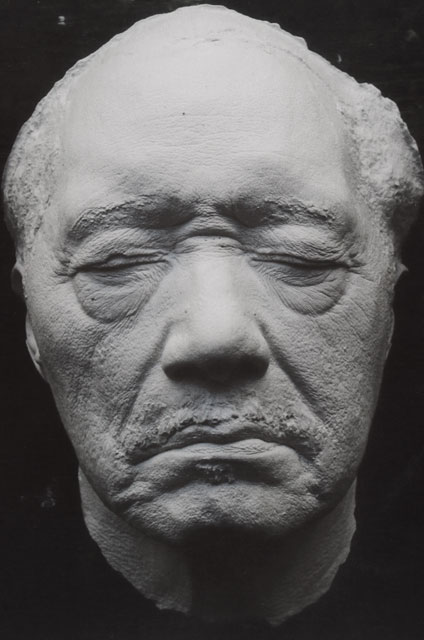

The life casts include masks of Bobby “Blue” Bland, Little Milton from Memphis, “Honeyboy” Edwards from Chicago, and Pinetop Perkins from Clarksdale, just to name a few – almost 60 musicians total.

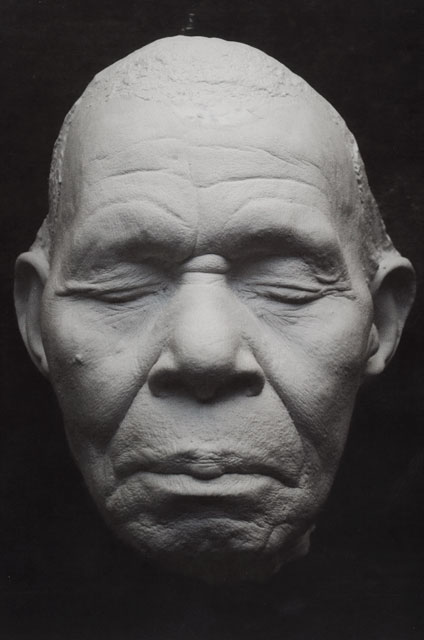

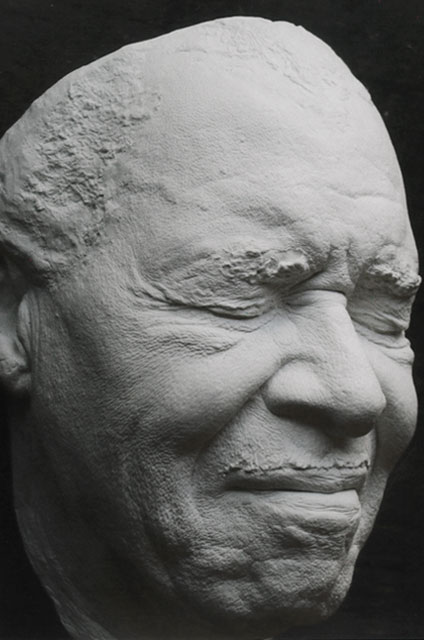

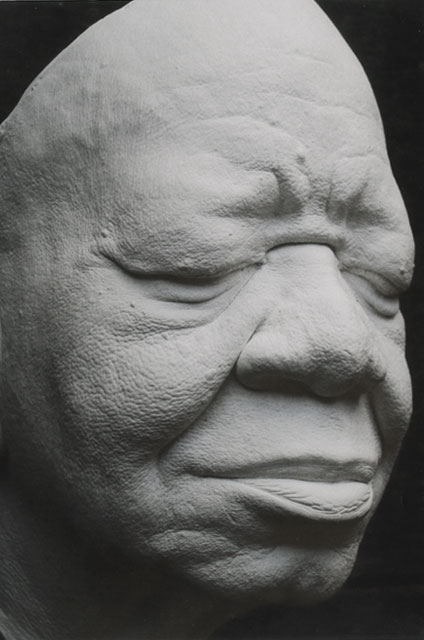

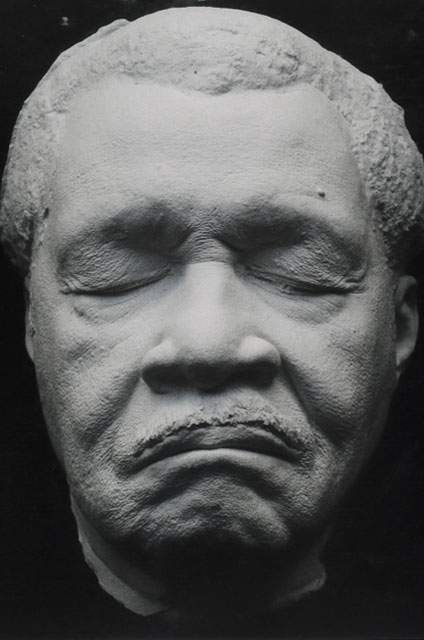

Dorothy Moore

Othar “Otha” Turner

ames Lewis Carter Ford AKA ” T-Model Ford”

“Little Bill” Wallace

Little Milton

R.L. Burnside

Q: What I didn’t mention is that Sharon McConnell-Dickerson is blind. She suffers from a degenerative eye disease called Uveitis. After she lost her ability to see, she discovered a new ability in art. Technically, she’s never fully seen her own work.

“When I woke up in Chicago visually impaired, I was shocked. I woke up and it was like a heavy fog had set in. There wasn’t any warning that I had any condition with my eyes. I just woke up and it was like a veil between me and the world. I had to some how get it together. Obviously, shock had set in and then survival. What am I going to do? What am I going to do? I just did it.”

Q: Before she lost her ability to see, over 25 years ago, she wasn’t an artist. In fact, she worked in corporate and private jets as a flight attendant and cook. She flew with executives and famous people such as: Barbara Bush, Donald and Ivana Trump, Al Haig, Henry Kissinger, and others.

“It was a really hard morning. I had to feel around for my shoes. I remember going downstairs to the lobby pretending to read a newspaper. I knew if I caught eye of someone, and didn’t respond, I may be found out. I was faking it pretty good. When they said, ‘Good morning.’ I would say ‘Good morning.’ and I followed them out. I couldn’t see the plane, nevermind the tail number. I don’t know how I made it that day on that plane.”

Q: What did the doctor say?

“Later, I went to an opthamologist and I was told I had a degenerative eye disease that would lead to total blindness. They couldn’t tell me when it would happen. They just said, ‘You could lose your sight tomorrow. You could lose it 10 years from now. But you will lose it.’ I did everything I could to prolong it. I tried drug therapy, surgeries, procedures… I didn’t respond to anything. I’ve been working on the Cast of Blues project for 14 years now. I kept going through those surgeries and those drug treatments. This was a whole new chapter in my life. I was reengineering my life. Moving on and finding new ability. The music and the musicians, and the people that I’ve met, are keeping me going. It was a beautiful distraction.”

Q: How would you describe your vision now?

“My central vision is completely gone. I have no sight out of my left eye. I have peripheral vision out of my right eye. Basically, I have light perception. If there’s a ray of sunlight coming from a window, I can tell that it’s sunny outside. I’m very light sensitive. I see dark but when I’m outside all I see is white.”

Q: What was your art background before you lost your vision?

“I had no art background, before I lost my sight. It was a friend that introduced me to sculpting. He came to my home and brought me a lump of clay, some tools and left me alone. Three hours later, I had formed what was a self portrait of myself. The clay transformed me. It gave me inspiration that I can do something. That experience made me feel something. I forgot about my disability or different ability. I felt new ability. I was like, ‘this is what I want to do. I want to learn how to sculpt.’ I was so proud of what I had done. As I look at it today, it’s beautiful to me. It is so raw and marks the beginning of my journey. It is perfectly imperfect.”

Blues can be heard in rock, soul, and in jazz. The music will last forever; but the musicians, that made it legendary, are dying.